- 首页

-

菜单

- 家园币

-

比特币

Financial Markets by TradingView

您正在使用一款已经过时的浏览器!部分功能不能正常使用。

- 主题发起人 ericguohy

- 发布时间 2008-05-25

更多选项

导出主题(文本)回复: 我的加国旅程(移民/商务旅行备忘录)

是的。

要全面考虑三个因素:

一、房价;二、加币和人民币的汇率;三、贷款利率

现在:房价已经降了,且为买方市场;以人民币换加币来买在汇率上比较合算;贷款利率低。。。

你还得考虑加币的因素,现在加币低。将来国内房价是有可能高,可加币没准也涨上去,加国的房价也涨了。

是的。

要全面考虑三个因素:

一、房价;二、加币和人民币的汇率;三、贷款利率

现在:房价已经降了,且为买方市场;以人民币换加币来买在汇率上比较合算;贷款利率低。。。

回复: 我的加国旅程(移民/商务旅行备忘录)

今天UBS发给我的简报里面有关加元的评论摘录如下:

题目:加元还没到走强的时候

我们预计加拿大元在未来几个月将面临压力,之后才会走上长期升值之路。加元走势受制于三个主要因素:其一,加元受益于石油价格高涨。中东局势的紧张导致石油价格小幅上升,推动美元/加元跌至1.2 以下。其二,加拿大经济对于大宗商品出口的依赖性较强,因此对于美国的需求以及美国经济状况非常敏感,近期数据显示加拿大商品出口在放缓。最近公布的加拿大失业率高达6.6%,超过市场一致预期的6.5%,有人预计失业率还将进一步恶化。最后,加元被视为“成长性货币”,有望从全球经济增长预期上升而获益,但目前显然还不到时候。我们预计今后几个月石油价格仍将维持低位,美国以及全球经济仍将低迷,从而将使美元/加元保持在1.25 附近。我们将关注即将于本周一公布的加拿大贷款专员调查( loan officer survey),从中将看出加拿大的信贷状况。

今天UBS发给我的简报里面有关加元的评论摘录如下:

题目:加元还没到走强的时候

我们预计加拿大元在未来几个月将面临压力,之后才会走上长期升值之路。加元走势受制于三个主要因素:其一,加元受益于石油价格高涨。中东局势的紧张导致石油价格小幅上升,推动美元/加元跌至1.2 以下。其二,加拿大经济对于大宗商品出口的依赖性较强,因此对于美国的需求以及美国经济状况非常敏感,近期数据显示加拿大商品出口在放缓。最近公布的加拿大失业率高达6.6%,超过市场一致预期的6.5%,有人预计失业率还将进一步恶化。最后,加元被视为“成长性货币”,有望从全球经济增长预期上升而获益,但目前显然还不到时候。我们预计今后几个月石油价格仍将维持低位,美国以及全球经济仍将低迷,从而将使美元/加元保持在1.25 附近。我们将关注即将于本周一公布的加拿大贷款专员调查( loan officer survey),从中将看出加拿大的信贷状况。

回复: 我的加国旅程(移民/商务旅行备忘录)

谢谢,可以参考。

谢谢,可以参考。

今天UBS发给我的简报里面有关加元的评论摘录如下:

题目:加元还没到走强的时候

我们预计加拿大元在未来几个月将面临压力,之后才会走上长期升值之路。加元走势受制于三个主要因素:其一,加元受益于石油价格高涨。中东局势的紧张导致石油价格小幅上升,推动美元/加元跌至1.2 以下。其二,加拿大经济对于大宗商品出口的依赖性较强,因此对于美国的需求以及美国经济状况非常敏感,近期数据显示加拿大商品出口在放缓。最近公布的加拿大失业率高达6.6%,超过市场一致预期的6.5%,有人预计失业率还将进一步恶化。最后,加元被视为“成长性货币”,有望从全球经济增长预期上升而获益,但目前显然还不到时候。我们预计今后几个月石油价格仍将维持低位,美国以及全球经济仍将低迷,从而将使美元/加元保持在1.25 附近。我们将关注即将于本周一公布的加拿大贷款专员调查( loan officer survey),从中将看出加拿大的信贷状况。

回复: 我的加国旅程(移民/商务旅行备忘录)

转一个1月17日《经济学人economists》有关加拿大油砂业的文章

A sticky ending for the tar sands

Jan 15th 2009 | CALGARY

From The Economist print edition

A boom based on extracting oil from tar sands turns bad

LOOK west from the office towers of the energy companies that dominate Calgary, and the view is spectacular: rolling prairies rise to tree-clad foothills, with the jagged, snow-capped peaks of the Rockies on the horizon. Looking down, however, is more unsettling. The city is dotted with motionless construction cranes poised over the pits of abandoned projects. A five-year energy boom here in the

administrative heart of Canada’s oil patch and in the tar sands far to the north has ended. The only debate is how painful and persistent the bust will benot just for the biggest city in Canada’s richest province, Alberta, but for the whole country.

Alberta, which produces two-thirds of Canada’s oil and gas, has been here before. The wrenching oil slump of the 1980s still looms large in the public consciousness. Companies fled the province and

thousands abandoned homes they could no longer afford. “The situation is much different this time,”insists the energy minister, Mel Knight, whose Progressive Conservative Party has ruled the province since 1971. Not all of the differences, however, are positive ones.

Mr Knight thinks continuing demand from places like China and India will mean that oil, and thus his province’s economy, will recover faster this time. However, two decades ago there was nothing like the current global credit crunch. Also, Alberta now extracts 60% of its crude from its tar sands (those in the

business think “oil sands” sounds nicer), a much bigger proportion than in the 1980s, and concern about the environment and carbon-based fuels is far stronger now. When news broke in December that construction had briefly halted on The Bow, the showpiece headquarters of EnCana, Canada’s largest independent energy firm, it sent shock waves across Calgary. The 58-storey tower designed by Lord Foster, a British architect, is both a symbol of Alberta’s new role as Canada’s economic engine and a poke in the eye for Toronto, the traditional corporate headquarters. The Bow’s owner says it still needs C$400m ($327m) of financing to finish the job. Up north in the tar sands, many projects are being postponed, as the credit crunch adds to the woes caused by low oil prices and high labour and material costs. Petro-Canada and its partners put the giant Fort Hills project on hold after the estimated costs rose to around C$25 billion from C$14.1 billion in just over a year.

Extracting oil from the sands took off in the late 1990s, boosted by technological advances that greatly reduced costs. Sitting on the equivalent of 173 billion barrels of crude, the provincial government

eyevine dreamed of making Alberta a new Saudi Arabia (with moose instead of camels). Although some, such as Peter Lougheed, a former premier, called for “orderly” development, a wild rush ensued, causing provincewide labour shortages. Even servers at fast-food restaurants had to be lured with an iPod or other inducements. Now, though, employment is slumping: Steve Vetter, a manager at a firm that services the gas industry, says it recently had 50 applicants for one job; two years ago it would have been lucky to get any.

Extracting oil from tar sands causes more carbon emissions than traditional drilling. At some projects, leaks of toxic material have polluted waterways. So even if the credit crunch eases and the oil price steadies, Canada’s tar sands may face tougher scrutiny from their main customer. The United States has hitherto been an enthusiastic buyer but the incoming Obama administration, packed with environmentalist hawks, may prove much less so, especially as the Democrats also control Congress.

Henry Waxman, a Californian green crusader, has become chairman of the House energy committee. He wrote part of an energy bill passed in 2007 that seemed to ban American government agencies from buying oil produced from the tar sands.

It will be a further damper on investment in Alberta if the Obama administration enforces the ban. Canada’s prime minister, Stephen Harper, who will meet Mr Obama soon after his inauguration, said this week that the tar sands would be one of the stickier subjects on their agenda.

On top of the oil bust, Canada’s other commodity exports, such as lumber, are also suffering collapsing demand. After years of good growth, the economy will shrink this year. Mr Harper says it will take up to five years of “big, comprehensive” government stimulus to dig it out of the deep, black hole it is in.

转一个1月17日《经济学人economists》有关加拿大油砂业的文章

A sticky ending for the tar sands

Jan 15th 2009 | CALGARY

From The Economist print edition

A boom based on extracting oil from tar sands turns bad

LOOK west from the office towers of the energy companies that dominate Calgary, and the view is spectacular: rolling prairies rise to tree-clad foothills, with the jagged, snow-capped peaks of the Rockies on the horizon. Looking down, however, is more unsettling. The city is dotted with motionless construction cranes poised over the pits of abandoned projects. A five-year energy boom here in the

administrative heart of Canada’s oil patch and in the tar sands far to the north has ended. The only debate is how painful and persistent the bust will benot just for the biggest city in Canada’s richest province, Alberta, but for the whole country.

Alberta, which produces two-thirds of Canada’s oil and gas, has been here before. The wrenching oil slump of the 1980s still looms large in the public consciousness. Companies fled the province and

thousands abandoned homes they could no longer afford. “The situation is much different this time,”insists the energy minister, Mel Knight, whose Progressive Conservative Party has ruled the province since 1971. Not all of the differences, however, are positive ones.

Mr Knight thinks continuing demand from places like China and India will mean that oil, and thus his province’s economy, will recover faster this time. However, two decades ago there was nothing like the current global credit crunch. Also, Alberta now extracts 60% of its crude from its tar sands (those in the

business think “oil sands” sounds nicer), a much bigger proportion than in the 1980s, and concern about the environment and carbon-based fuels is far stronger now. When news broke in December that construction had briefly halted on The Bow, the showpiece headquarters of EnCana, Canada’s largest independent energy firm, it sent shock waves across Calgary. The 58-storey tower designed by Lord Foster, a British architect, is both a symbol of Alberta’s new role as Canada’s economic engine and a poke in the eye for Toronto, the traditional corporate headquarters. The Bow’s owner says it still needs C$400m ($327m) of financing to finish the job. Up north in the tar sands, many projects are being postponed, as the credit crunch adds to the woes caused by low oil prices and high labour and material costs. Petro-Canada and its partners put the giant Fort Hills project on hold after the estimated costs rose to around C$25 billion from C$14.1 billion in just over a year.

Extracting oil from the sands took off in the late 1990s, boosted by technological advances that greatly reduced costs. Sitting on the equivalent of 173 billion barrels of crude, the provincial government

eyevine dreamed of making Alberta a new Saudi Arabia (with moose instead of camels). Although some, such as Peter Lougheed, a former premier, called for “orderly” development, a wild rush ensued, causing provincewide labour shortages. Even servers at fast-food restaurants had to be lured with an iPod or other inducements. Now, though, employment is slumping: Steve Vetter, a manager at a firm that services the gas industry, says it recently had 50 applicants for one job; two years ago it would have been lucky to get any.

Extracting oil from tar sands causes more carbon emissions than traditional drilling. At some projects, leaks of toxic material have polluted waterways. So even if the credit crunch eases and the oil price steadies, Canada’s tar sands may face tougher scrutiny from their main customer. The United States has hitherto been an enthusiastic buyer but the incoming Obama administration, packed with environmentalist hawks, may prove much less so, especially as the Democrats also control Congress.

Henry Waxman, a Californian green crusader, has become chairman of the House energy committee. He wrote part of an energy bill passed in 2007 that seemed to ban American government agencies from buying oil produced from the tar sands.

It will be a further damper on investment in Alberta if the Obama administration enforces the ban. Canada’s prime minister, Stephen Harper, who will meet Mr Obama soon after his inauguration, said this week that the tar sands would be one of the stickier subjects on their agenda.

On top of the oil bust, Canada’s other commodity exports, such as lumber, are also suffering collapsing demand. After years of good growth, the economy will shrink this year. Mr Harper says it will take up to five years of “big, comprehensive” government stimulus to dig it out of the deep, black hole it is in.

回复: 我的加国旅程(移民/商务旅行备忘录)

“转一个1月17日《经济学人economists》有关加拿大油砂业的文章

Even servers at fast-food restaurants had to be lured with an iPod or other inducements. Now, though, employment is slumping: Steve Vetter, a manager at a firm that services the gas industry, says it recently had 50 applicants for one job; two years ago it would have been lucky to get any.”

“转一个1月17日《经济学人economists》有关加拿大油砂业的文章

Even servers at fast-food restaurants had to be lured with an iPod or other inducements. Now, though, employment is slumping: Steve Vetter, a manager at a firm that services the gas industry, says it recently had 50 applicants for one job; two years ago it would have been lucky to get any.”

回复: 我的加国旅程(移民/商务旅行备忘录)

转一个《经济学人》有关北电破产的文章。

随着百年企业北电的破产,加拿大的全球性大企业,只剩下生产蓝莓手机的RIM,以及生产飞机的庞巴迪了。随着近年来政府政策向资源性产业的偏移,加拿大制造业和高科技产业的竞争力下降了。

本来中国华为要去收购北电的,可是没有获批。

Nortel: The bigger they come

Jan 15th 2009

From The Economist print edition

Canada’s technology icon is unlikely to emerge from bankruptcy protection

IN THE end the question was not if, but when. On January 14th Nortel, a troubled Canadian maker of telecoms equipment, filed for bankruptcy protection, making it the first big technology firm to succumb to the recession. “Nortel must be put on a sound financial footing once and for all,” explained Mike Zafirovsky, its chief executive.

It marks the end of a breathtaking fall. Nortel, a high-flyer during the internet boom, was once Canada’s largest company, employing 95,000 people worldwide and boasting a stockmarket value, at its peak, of C$366 billion ($251 billion), accounting for more than one-third of the value of the entire Toronto Stock Exchange. Just before the filing this week, its workforce had shrunk to 26,000 and its stockmarket capitalisation to a mere C$191m ($156m).

The immediate cause of Nortel’s demise is the recession, which hit it particularly hard. In November Nortel posted a third-quarter loss of $3.4 billion. Revenue in its core business, which sells switching gear to telephone companies, fell by 24%. But the roots of Nortel’s troubles go deeper. It never really recovered from the bursting of the internet bubble in 2000-2001, followed by an accounting scandal in 2004.

Will other big technology firms follow it into bankruptcy? Not necessarily. Although its rivals are not doing too well, they are stronger. In December Alcatel-Lucent said demand for its products would fall by 8-12% next year, and it would not make much of an operating profit before 2010. Even Motorola and Sun Microsystems, embattled makers of telecoms equipment and high-end computers respectively, should be able to make it through the recession, provided they are not taken over or broken up by their own management. Both firms have plenty of cash in the bank.

Still, Nortel could become a model. Its filing was a “strategic move”, says Richard Windsor, an analyst at Nomura Securities. With $2.4 billion in the bank, Nortel could have limped along for a while. But it went for bankruptcy protection now, he says, so it would not have to do it in total desperation when the money had run out. Will it emerge in one piece? Probably not, says Mr Windsor. Its parts are likely to be sold, perhaps to Huawei Technologies, a Chinese rival which has been looking to boost its presence in North America for some time. It is a sorry end for a once-proud Canadian technology icon, but this way investors will at least get some of their money back.

转一个《经济学人》有关北电破产的文章。

随着百年企业北电的破产,加拿大的全球性大企业,只剩下生产蓝莓手机的RIM,以及生产飞机的庞巴迪了。随着近年来政府政策向资源性产业的偏移,加拿大制造业和高科技产业的竞争力下降了。

本来中国华为要去收购北电的,可是没有获批。

Nortel: The bigger they come

Jan 15th 2009

From The Economist print edition

Canada’s technology icon is unlikely to emerge from bankruptcy protection

IN THE end the question was not if, but when. On January 14th Nortel, a troubled Canadian maker of telecoms equipment, filed for bankruptcy protection, making it the first big technology firm to succumb to the recession. “Nortel must be put on a sound financial footing once and for all,” explained Mike Zafirovsky, its chief executive.

It marks the end of a breathtaking fall. Nortel, a high-flyer during the internet boom, was once Canada’s largest company, employing 95,000 people worldwide and boasting a stockmarket value, at its peak, of C$366 billion ($251 billion), accounting for more than one-third of the value of the entire Toronto Stock Exchange. Just before the filing this week, its workforce had shrunk to 26,000 and its stockmarket capitalisation to a mere C$191m ($156m).

The immediate cause of Nortel’s demise is the recession, which hit it particularly hard. In November Nortel posted a third-quarter loss of $3.4 billion. Revenue in its core business, which sells switching gear to telephone companies, fell by 24%. But the roots of Nortel’s troubles go deeper. It never really recovered from the bursting of the internet bubble in 2000-2001, followed by an accounting scandal in 2004.

Will other big technology firms follow it into bankruptcy? Not necessarily. Although its rivals are not doing too well, they are stronger. In December Alcatel-Lucent said demand for its products would fall by 8-12% next year, and it would not make much of an operating profit before 2010. Even Motorola and Sun Microsystems, embattled makers of telecoms equipment and high-end computers respectively, should be able to make it through the recession, provided they are not taken over or broken up by their own management. Both firms have plenty of cash in the bank.

Still, Nortel could become a model. Its filing was a “strategic move”, says Richard Windsor, an analyst at Nomura Securities. With $2.4 billion in the bank, Nortel could have limped along for a while. But it went for bankruptcy protection now, he says, so it would not have to do it in total desperation when the money had run out. Will it emerge in one piece? Probably not, says Mr Windsor. Its parts are likely to be sold, perhaps to Huawei Technologies, a Chinese rival which has been looking to boost its presence in North America for some time. It is a sorry end for a once-proud Canadian technology icon, but this way investors will at least get some of their money back.

回复: 我的加国旅程(移民/商务旅行备忘录)

有意思,关注!

有意思,关注!

回复: 我的加国旅程(移民/商务旅行备忘录)

完全同意楼主的看法。 我考了两次鸭,第一次没做任何准备,结果G类阅读只考了5.5(最不可能的事情),口语却达到7, 其他两项均为6.5; 第二次,主要是为了申请澳大利益的移民(尽管已经06年8月已经提交了加拿大的申请, 为了不把鸡蛋都放在一个篮子里),做完职业评估后,参加了08年6月14号的雅思,口语真让我吃惊:LRWS -> 7.5, 7.5, 6.5, 6. 总分125分(技术移民要求120分,雅思每个单项最低要求:6分)。 所以口语的变数太大了,一定程度上取决于面试你的那位考官。回想起来第二次口语考试我主要失败在太诚实了,当考官问我童年时期最爱看的电视节目是什么?我说对不起,我在偏远农村长大,那是连居民用电都没有(知道我上大学的时候才通的电),哪还有条件看电视节目呢。但我交流上一点问题都没有,因为工作语言就是英语。当时瞎编一下故事就好了。

说实在的,4个7真的很难。不知道你的基础怎么样,因此也就不知道你将着重在哪方面进行复习。记得2月初我考雅思的时候,中午是跟一个从澳大利亚留学回来的北京男孩一起吃饭。他是第二次考雅思,我也是第一次从他的口中听到“4个7很难”这个论断。他说,家里花那么多钱供他留学,不办个移民没法交代,因此必须要办移民。澳大利亚移民不同于加拿大移民,只要4个7,半年就能办成,没有4个7,多长时间都办不成。像他这样情况的人很多,因此雅思考官在评分时,对4个7卡得很严,轻易是拿不到的。毕竟,澳大利亚也是雅思的主办方之一。

雅思往往在你最把握的地方给你一个以外,我的情况可以作为印证:其它的都是7分以上,唯独口语,只拿到6.5。本来我的口语基础很好,平常也经常跟老外交流,况且考试的时候自我感觉表现也很好,但是只拿到6.5.

在论坛看到另一个人,情况差不多,他每天都要拿英文写好多东西,但是偏偏其它都7分以上,写作只拿到6.5。

你的情况,可能是移民分不够,如果雅思考试成绩不能给你加上需要的分数的话,可以在考完雅思之后,花半年时间突击学一下法语,只要考试成绩能给你加上2分,雅思拿到3个7又有何妨?

完全同意楼主的看法。 我考了两次鸭,第一次没做任何准备,结果G类阅读只考了5.5(最不可能的事情),口语却达到7, 其他两项均为6.5; 第二次,主要是为了申请澳大利益的移民(尽管已经06年8月已经提交了加拿大的申请, 为了不把鸡蛋都放在一个篮子里),做完职业评估后,参加了08年6月14号的雅思,口语真让我吃惊:LRWS -> 7.5, 7.5, 6.5, 6. 总分125分(技术移民要求120分,雅思每个单项最低要求:6分)。 所以口语的变数太大了,一定程度上取决于面试你的那位考官。回想起来第二次口语考试我主要失败在太诚实了,当考官问我童年时期最爱看的电视节目是什么?我说对不起,我在偏远农村长大,那是连居民用电都没有(知道我上大学的时候才通的电),哪还有条件看电视节目呢。但我交流上一点问题都没有,因为工作语言就是英语。当时瞎编一下故事就好了。

回复: 我的加国旅程(移民/商务旅行备忘录)

A pragmatic budget has given Stephen Harper’s government a new lease of lifebut not necessarily a long one

MORE than in many countries, in Canada the question of how to respond to the world recession has become muddied by party politics. During the campaign for last autumn’s general election, Stephen Harper, the Conservative prime minister, ridiculed the opposition for daring to suggest that his government might post a budget deficit in a country that has come to prize fiscal virtue. Having won a second term, though once again without a parliamentary majority, Mr Harper promptly almost lost it over

a government economic statement in late November. In this his finance minister, Jim Flaherty, again rejected the need for fiscal stimulus but threw in some partisan measures. That prompted the disparate opposition to gang up to try to oust Mr Harpera fate he evaded only by persuading the governorgeneral, who acts as Canada’s head of state, to shut down parliament for seven weeks.

In that period the economy has slithered towards recession. So this week’s budget was of more than usual interest. In the event, Mr Flaherty showed a surer touch than in November. Jettisoning his party’s ideological commitment to small government, he came up with new spending and tax breaks worth C$40 billion ($33 billion) over the next two years. Much of the money will go on maintaining roads, railways and ports and in encouraging home improvements. The government is also adding C$50 billion to its C$75 billion fund to buy mortgage-backed securities from banks, to encourage them to lend. For the first time since 1996 the federal budget will move into deficit, with a shortfall of C$34 billion in the fiscal year

starting in April. Deficits will total some C$85 billion before the federal finances return to the black in four years time, Mr Flaherty forecasts.

Previous Liberal governments worked hard to cure Canada of an addiction to deficit financing. In losing his fiscal virginity, Mr Flaherty blamed “the synchronised global recession”. Certainly Canada is vulnerable: it has been hurt by recession in the United States, which buys three-quarters of its exports, and by falls in the prices of its commodities. Private-sector economists consulted by the government expect the economy to contract by 0.8% this year, bouncing back to growth of 2.4% in 2010. The darkening economic outlook, especially in Ontario where the car industry is oncentrated, has softened public opposition to deficits.

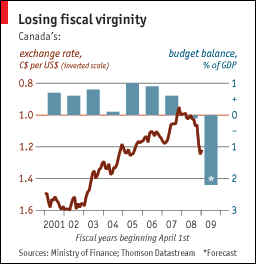

But has Mr Flaherty got the dose right? The economy remains relatively strong. Canada’s banks are much better regulated, and sounder, than their American counterparts. The central bank began to inject liquidity into the banking system a year ago, and has slashed its benchmark interest rate to just 1%. A weaker currency (see chart) will help exporters. Mark Carney, the central bank’s governor, expects the economy to start to recover late this year (though he says this may not be apparent until early 2010). If so, monetary policy may deserve more of the credit than fiscal stimulus.

The government’s more immediate concern is survival. On this it may have little to fear for now. The separatist Bloc Québécois and the leftist New Democrats (with 86 seats between them) both said they would vote against the budget. But Michael Ignatieff, the new leader of the Liberals, whose 77 of the 308 seats in the House of Commons are vital, said he would back the budget, provided Mr Flaherty offers quarterly reports on how the extra money is being spent. “We’re putting the government on probation,” he said.

Mr Ignatieff is unenthusiastic about his predecessor’s idea of an opposition coalition. It suits the Liberals better to let the Conservatives take the blame for the recession while rebuilding their own finances, organisation and ideas. As for Mr Harper, while the budget shows that he is a pragmatist, it is not popular with some in his own party. Since November, his authority is no longer unassailable. He is living on borrowed time as well as money.

A pragmatic budget has given Stephen Harper’s government a new lease of lifebut not necessarily a long one

MORE than in many countries, in Canada the question of how to respond to the world recession has become muddied by party politics. During the campaign for last autumn’s general election, Stephen Harper, the Conservative prime minister, ridiculed the opposition for daring to suggest that his government might post a budget deficit in a country that has come to prize fiscal virtue. Having won a second term, though once again without a parliamentary majority, Mr Harper promptly almost lost it over

a government economic statement in late November. In this his finance minister, Jim Flaherty, again rejected the need for fiscal stimulus but threw in some partisan measures. That prompted the disparate opposition to gang up to try to oust Mr Harpera fate he evaded only by persuading the governorgeneral, who acts as Canada’s head of state, to shut down parliament for seven weeks.

In that period the economy has slithered towards recession. So this week’s budget was of more than usual interest. In the event, Mr Flaherty showed a surer touch than in November. Jettisoning his party’s ideological commitment to small government, he came up with new spending and tax breaks worth C$40 billion ($33 billion) over the next two years. Much of the money will go on maintaining roads, railways and ports and in encouraging home improvements. The government is also adding C$50 billion to its C$75 billion fund to buy mortgage-backed securities from banks, to encourage them to lend. For the first time since 1996 the federal budget will move into deficit, with a shortfall of C$34 billion in the fiscal year

starting in April. Deficits will total some C$85 billion before the federal finances return to the black in four years time, Mr Flaherty forecasts.

Previous Liberal governments worked hard to cure Canada of an addiction to deficit financing. In losing his fiscal virginity, Mr Flaherty blamed “the synchronised global recession”. Certainly Canada is vulnerable: it has been hurt by recession in the United States, which buys three-quarters of its exports, and by falls in the prices of its commodities. Private-sector economists consulted by the government expect the economy to contract by 0.8% this year, bouncing back to growth of 2.4% in 2010. The darkening economic outlook, especially in Ontario where the car industry is oncentrated, has softened public opposition to deficits.

But has Mr Flaherty got the dose right? The economy remains relatively strong. Canada’s banks are much better regulated, and sounder, than their American counterparts. The central bank began to inject liquidity into the banking system a year ago, and has slashed its benchmark interest rate to just 1%. A weaker currency (see chart) will help exporters. Mark Carney, the central bank’s governor, expects the economy to start to recover late this year (though he says this may not be apparent until early 2010). If so, monetary policy may deserve more of the credit than fiscal stimulus.

The government’s more immediate concern is survival. On this it may have little to fear for now. The separatist Bloc Québécois and the leftist New Democrats (with 86 seats between them) both said they would vote against the budget. But Michael Ignatieff, the new leader of the Liberals, whose 77 of the 308 seats in the House of Commons are vital, said he would back the budget, provided Mr Flaherty offers quarterly reports on how the extra money is being spent. “We’re putting the government on probation,” he said.

Mr Ignatieff is unenthusiastic about his predecessor’s idea of an opposition coalition. It suits the Liberals better to let the Conservatives take the blame for the recession while rebuilding their own finances, organisation and ideas. As for Mr Harper, while the budget shows that he is a pragmatist, it is not popular with some in his own party. Since November, his authority is no longer unassailable. He is living on borrowed time as well as money.

Similar threads

- 6

2024-03-30有新回复

全楼:0.01

Bingoye

家园推荐黄页

家园币系统数据

- 家园币池子报价

- 0.0097加元

- 家园币最新成交价

- 0.0101加元

- 家园币总发行量

- 1106666家园币

- 加元现金总量

- 12065.9加元

- 家园币总成交量

- 4098206.67家园币

- 家园币总成交价值

- 384692.02加元

- 池子家园币总量

- 396336.11家园币

- 池子加元现金总量

- 3850.24加元

- 池子币总量

- 35214.19

- 1池子币现价

- 0.2187加元

- 池子家园币总手续费

- 5731.58JYB

- 池子加元总手续费

- 595.28加元

- 入池家园币年化收益率

- 0.38%

- 入池加元年化收益率

- 4.06%

- 微比特币最新报价

- 0.133430加元

- 毫以太币最新报价

- 5.03858加元

- 微比特币总量

- 0.354795BTC

- 毫以太币总量

- 0.219250ETH

- 家园币储备总净值

- 532,417.01加元

- 家园币比特币储备

- 3.4200BTC

- 家园币以太币储备

- 15.1ETH

- 比特币的加元报价

- 133,430.00加元

- 以太币的加元报价

- 5,038.58加元

- USDT的加元报价

- 1.40473加元

- 交易币种/月度交易量

- 手续费

- 家园币

- 0.1%(0.01%-1%)

- 加元交易对(比特币等)

- 1%-2%

- USDT交易对(比特币等)

- 0.1%-0.6%